Tomorrow, we’re swearing in Tishaura Jones as Mayor here in St. Louis. She’ll be the first Black woman to hold the City’s top job. On the eve of this historic moment, I’m sharing a special edition of River City Data in collaboration with my friends Andrew Arkills and Ben Conover. Both Andrew and Ben are experienced data scientists and have been active in analyzing St. Louis political data for some time now. Each has put together an interactive dashboard of results, Andrew for the Mayoral race between Jones and Cara Spencer, and Ben for the SLPS School Board election. I hope you find their maps and analyses informative! - Chris

Proposition D

Chris

This latest pair of primary and general elections were the first after the passage of Proposition D. The changes, which passed during the November 2020 election, created a system of non-partisan elections.

During the primary, held on March 2nd, voters no longer voted for either Democrat or Republican candidates. Instead, they could select (or “approve of”) as many candidates as they wished for each race. The candidates with the two highest vote totals in each race then proceeded to the general election.

The result was that, unlike past general elections, where the result was often a foregone conclusion because of the paucity of Republican voters in St. Louis, we saw a raft of competitive races for not just Mayor but also Board of Aldermen seats.

Breaking Down the Mayoral Race

Andrew Arkills

This system described by Chris above saw Mayor-elect Jones and Alderwoman Cara Spencer emerge from a field of four candidates in the primary, which also featured Board of Aldermen President Lewis Reed, as well as businessman Andrew Jones. Voters approved of Tishaura Jones and Cara Spencer at a rate of 56.96% and 46.35%, respectively, Reed and A. Jones received approval votes from 38.56% and 14.42% of voters. The final vote in the general election was 51.70% for Tishaura Jones, and 47.75% for Cara Spencer.

On its face, this would appear to be a tightening in the race, and in some ways it was. There were likely some voters who voted in the primary and had neither T, Jones, nor Spencer on their approval slate. These voters, if they returned to vote in the runoff, would have been up for grabs and would have re-aligned themselves with a new candidate. Additionally, voters who voted in the primary and had both T. Jones and Spencer on their approval slate would have needed to choose one candidate in the general.

The additional wild card for the general election was that turnout increased from 22.14% in the primary, to 29.15% in the general, meaning that the general election electorate was 31.66% larger than the electorate in the primary. These new voters in this cycle were also up for grabs and were fought for by both candidates.

As I’ll explore below, the geographic breakdown of where the candidates were successful in retaining their original voters, as well as increasing their voter pool showed some new patterns emerging in voter behavior that may signal a realignment in the mental and actual maps that have driven politics in this city for the past several decades, or they could be a one-off blip, from which we will return to old alliances.

The interactive version of the maps and graphs that follow can be found here.

North, South Central, and Far South

For the purposes of analyzing this race from a geographic perspective, I split the 28 wards of St. Louis into three distinct clusters, which we can refer to as North, South Central, and Far South. The North cluster consists of wards primarily situated north of Delmar, for this analysis, this includes the 19th Ward. The South Central cluster consists of wards primarily situated between Delmar and Chippewa. Finally, the Far South cluster consists of wards primarily situated south of Chippewa, including the 20th Ward. It should be noted that the last two could easily have been replaced by an east/west border, running roughly down Kingshighway from Delmar.

These clusters offered a decently equal distribution of votes to the North (15,767 votes) and the Far South (14,805), leaving the 27,778 votes in the South Central cluster as the largest chunk of votes up for grabs. This cluster had the most votes, but it may not have been the decisive battleground many are assuming it was, at least not on its own.

What Happened?

In the above graphic, we see Mayor-elect Jones, in blue, made a clean sweep of all of the wards in the North cluster, she did so in an overwhelming fashion, winning 12,698 of the 15,767 votes (80.54%) cast in that cluster. Conversely, Alderwoman Spencer did very well in the Far South cluster, garnering 9,970 of the 14,805 votes (67.34%) cast there. Crucially, she did not sweep these wards, with Jones winning Ward 25 and Ward 20, Spencer’s home ward. Additionally, Jones was also able to keep the race south of Chippewa from being a rout, picking up 4,709 of the 14,805 (31.81%) votes. This proved very important to the final outcome. In the final cluster, the South Central cluster, Spencer was able to win a majority of the votes, and five of the eight wards. However, she did not do so by large margins, winning 14,884 of the 27,778 votes (53.58%) in this cluster. The final margin for Jones, by cluster, is as follows:

North: 9,687

South Central: -2,125

Far South: -5,261

The final winning total margin of 2,301 for Jones was built on the strength of both the turnout north of Delmar, as well as the percentage of voters that Jones was able to win to her side there. She held her own in the South Central cluster, and kept the race in the Far South cluster from being an inverse of the result in the North cluster.

Turnout, Turnout, Turnout

As we can see in the above graphic, the number of ballots cast in the general, relative to the primary increased by at least 20% in every ward. Additionally, high turnout wards such as 6, 8, and 15 did not see huge increases in turnout relative to other wards, which made the playing field more level in terms of wards being able to affect the race to the same degree than it would have been had those wards seen turnout increases of 30-40% as occurred in many other wards.

Overall turnout is a good signal of the overall interest in the race, but just as important, and where races are won or lost, is who voters turn out for. This contest saw both candidates increasing their overall vote count from the primary, which is to be expected with the increased overall turnout. Where they added voters, and how many, is where the race was decided.

Mayor-elect Jones did an excellent job of adding votes in the North cluster. She was able to turn out at least 20% more voters to her side in every single ward in the cluster. She added votes by smaller margins in the South Central cluster, and was able to add 20-40% more voters in the two Far South wards she won, 20 and 25.

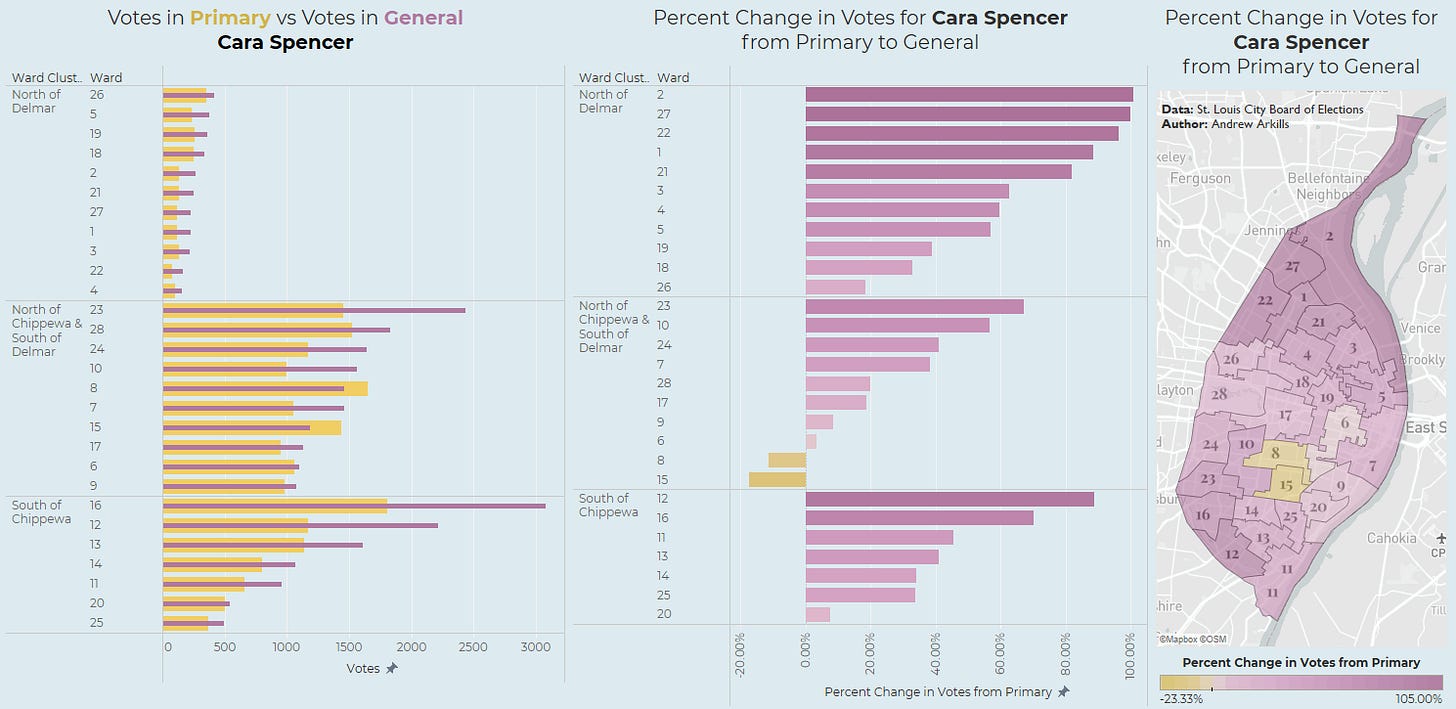

Alderwoman Spencer was also adept at adding voters, but did not get nearly the turnout she needed to see in the North cluster to close the gap with Mayor-elect Jones. Spencer was able to build on past success in wards such as 12,16, and 23, making massive gains in wards that had given her broad support in the approval voting round. When comparing the preceding two graphics, we are able to discern that the relatively broad nature of the support for Mayor-elect Jones allowed her to keep in close south of Delmar, and run to victory on her strong support in that North cluster.

Of additional note, and this is more of a curiosity than a decisive factor all by itself, but in wards 8 and 15, Spencer actually lost votes from the primary to the general. This would seem to indicate that when voters had to choose between Spencer and Jones, who both received broad approval in those wards in the primary, they broke for Jones. This switch was not singularly decisive in this race, but may be worth keeping an eye on, both as governing coalitions at the Board of Aldermen emerge, as well as for the impact of this bloc of voters on future city-wide contests.

Where Did The Votes Come From?

In the following graphics, we see the wards from which the candidates received various percentages of the overall votes they each received. The Jones map displays the percentage of votes that Jones received which came from each ward, the Spencer map shows the same for her votes. In these maps, we see the same trends we’ve observed previously, that Jones was able to keep it close in the South Central cluster, and that she had a large number of votes being banked in the North cluster. This overcame the 2:1 margin she lost by in the Far South cluster.

Mayor-elect Jones was able to spread her votes around the city to a greater degree than Alderwoman Spencer. This is not necessarily important to the outcome of this election, but may be a useful metric she can use when having discussions with various alderpersons in seeking to build coalitions and support for initiatives she undertakes. To illustrate this, the war contributing the lowest percentage of Mayor-elect Jones’s overall votes was Ward 12, at 1.91%. This was the only ward that contributed less than 2% of her overall votes. Alderwoman Spencer, conversely, was unable to obtain more than 2% of her total votes of any single ward in the North cluster.

Final Thoughts

This election pivoted on the degree to which the wards in the North cluster were able to flex their collective political muscle, which had been perceived to be waning. This election showed that a candidate which this cluster supports, and who has at least moderate appeal in the rest of the city, can still emerge victorious in heavily contested city-wide races. Whether this is a feature of the new approval system, only time will tell. The patterns that have developed in this city’s political geography over the past several months will be interesting to watch as the city continues to rapidly change, across almost every socio-economic measure.

Breaking Down the SLPS Race

Ben Conover

Disclosure: Ben is a part of Solidarity with SLPS, which graded candidates based on their willingness to accept money from pro-charter school organizations and their policy stances about charters in St. Louis.

Overview

The SLPS dashboard contains a number of different visualizations:

Turnout Percentage By Ward

Total Votes per Card by Ward - this represents the number of candidates selected per ballot, since each voter could select up to three candidates

Votes per Registered Voter

Candidate Votes per Cards Cast - the percentage of cards cast where the candidate selected on the toggle received a vote by Ward

Votes Percentage on Uniform Distribution - the percentage of the vote above or below 10% of the candidate selected on the toggle received by Ward. 10% represents what percentage each candidate would receive if the votes were uniformly distributed since there were 10 candidates.

Data on the Progress STL, American Federation of Teachers, and Democratic Socialists of America slates

Winning Candidates

Racially divided electorate persists but with notable exceptions

For a quick snapshot, see the difference between strong wards for the Progress STL Slate (all Black women) and the AFT Slate (all white candidates). Voting patterns largely followed the racial makeup of the wards between the two slates. Notable exceptions include:

Natalie Vowell: the incumbent, who won 16 out of 28 wards. Vowell is a white woman but lives in North St. Louis.

Emily Hubbard: Hubbard performed above the average in Wards 3, 5, and 26 which are predominantly black. While she focused her platform on racial equity, I would speculate that her last name (though she is not related) helped her in these Wards represented by Shameem Clark Hubbard and (now formerly) Tammika Hubbard, respectively.

Alisha Sonnier: Sonnier performed well in a number of South St. Louis Wards that Mayor-elect Tishaura Jones performed well in, as well as being bolstered by endorsements in the 14th, 15th, and 24th. Jones endorsed Sonnier and campaigned together on Election Day.

Wards 2 and 15: A Tale of Two Slates

Both Wards 2 and 15 outperformed other wards in votes per card cast. In Ward 2, AFT had poll workers at Nance School all day, leading to a strong performance for their slate in that Ward – you will notice that Ward 2 looks like an anomaly on the maps (and precinct data confirms the impact at Nance especially). In Ward 15, Alderwoman Megan Green and the 15th Ward Democrats endorsed Vowell, Davis, and Sonnier. That slate garnered over 60% of the total votes, significantly outperforming other Ward endorsements.

An Extremely Tight Race…

Only 29 votes separated Matt Davis and Alisha Sonnier citywide (~1 vote per Ward), who drew their votes out of almost entirely opposite Wards (save the 15th). Fifth place finisher Emily Hubbard was only 114 votes behind Davis (~4 votes per Ward). Sonnier was bolstered by the Progress STL mailers and Mayor-elect Jones’ endorsement, while Davis was bolstered by AFT and DSA endorsements and Hubbard received the Post-Dispatch and DSA endorsements.

…except for Vowell and Cousins

Vowell finished in first or a very close second place in 19 out of 28 wards citywide. She blew out her nearest competition (Cousins) by nearly 5,000 votes. Cousins ran up her vote tally in North St. Louis, winning 9 out of 28 wards citywide, while mitigating losses in South St. Louis, finishing in a clear second place.

What Happens Next?

With Vowell returning to the school board, and Davis and Cousins replacing Board President Dorothy Rohde-Collins and long-serving member Susan Jones, there’s potential for a very new look board on April 27th. Further, school board member Adam Layne has been tapped to replace Mayor-elect Jones as Treasurer, likely opening up his slot on the school board. I’d speculate we will see Sonnier replace Layne given her closeness with the Mayor-elect. Whoever replaces Layne will be up for election in April 2023 (along with Mayor Krewson’s appointment Regina Fowler), while the next school board election will be in November 2022 for the positions currently held by Donna Jones and Dr. Joyce Roberts.

With such a tight race, I fully expect the next two elections to see even more dark money on the pro-privatization side and the defense of public education to get increasingly more difficult and costly. Candidates who support privatization via charter schools were bolstered by Progress St. Louis’ spending an estimated six-figures worth on mailers citywide. This spending was (just barely, in Davis’ case) neutralized by support from the local teachers’ union (American Federation of Teachers Local 420), Coalition of Black Trade Unionists, Ecumenical Council, and the Democratic Socialists of America. Watch for these trends to continue in coming cycles.

If you like what you see here and don’t already, please subscribe!