In this week’s edition of River City Data, I share an update on overall numbers and the direction new case counts are headed in Missouri, provide a resource for digesting election data in the “Into the Weeds” section, and share my interview with SLU colleague Dr. Fred Buckhold. Enjoy! - Chris

COVID-19 by the Numbers

Total cases in MO: 184,839 (+12,972 from last Friday)

7-day average of new cases per day in MO: 2,218.29 (+346.43 from last Friday)

Counties with the highest per capita rates of new cases per day this past week:

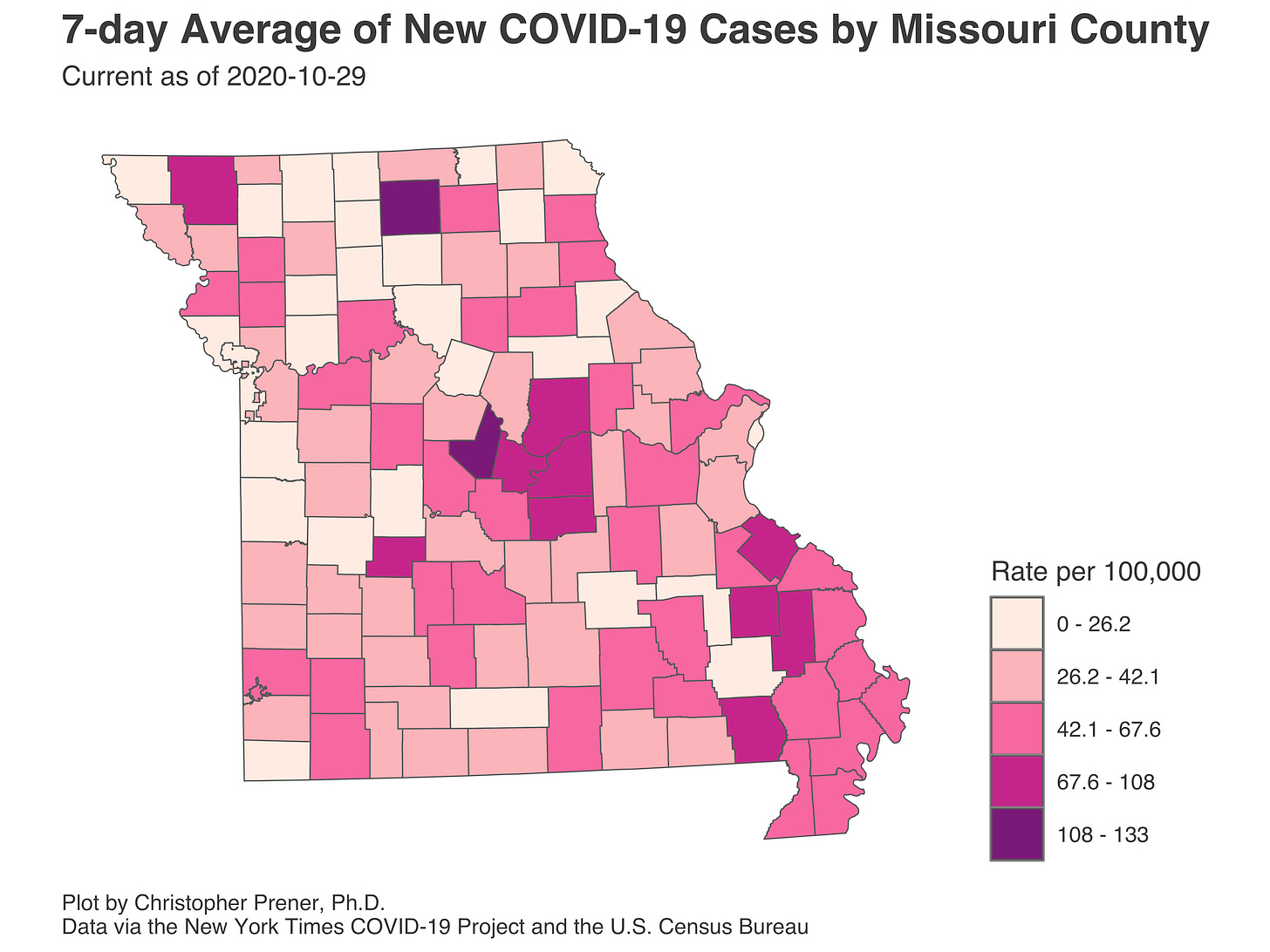

Sullivan (133.43 per 100,000), Moniteau (125.33), Callaway (90.16), Hickory (88.45), Cole (87.31), and Bollinger (87.24)

Total deaths in MO: 2,978 (+214 from last Friday)

7-day average of new deaths per day in MO: 29.00 34.86 (+4.29 from last Friday)

These numbers are current as of Thursday, October 29th. Additional statistics, maps, and plots are available on my COVID-19 tracking site.

New on the COVID-19 Tracking Site

In the past week, I’ve primarily been focused on expanding access to ZIP code data. I’ve been able to initiate background data collection for all Illinois ZIP codes, thanks to the trio of Saint Louis University computer science students working with me this year. I’ve also started collecting data for Warren and Lincoln counties, but there have been some challenges. I’m hoping to be able to share these data soon!

Summary for the Week Ending October 30th

My focus for this week’s summary is on the increasing pace of new cases and hospitalizations. I’ll start with new cases. Our statewide seven-day average has jumped up to a new all-time high of 2,218.29 cases for the last seven days.

One caution - I don’t think we can make apples-to-apples comparisons with the seven-day averages we saw in March, April, and May. The testing environment was too limited then and dramatically understated the number of cases in Missouri. In April, the CDC conducted an extensive seroprevalence survey here. They found that the number of people with anti-bodies for SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19) was twenty-four times higher than what case counts suggested at the time.

I do, however, think comparisons to the last couple of months are valid. Since late August, our numbers statewide, and in what I call, very inelegantly, “Outstate Missouri” (counties outside the St. Louis and Kansas City metros), have steadily climbed.

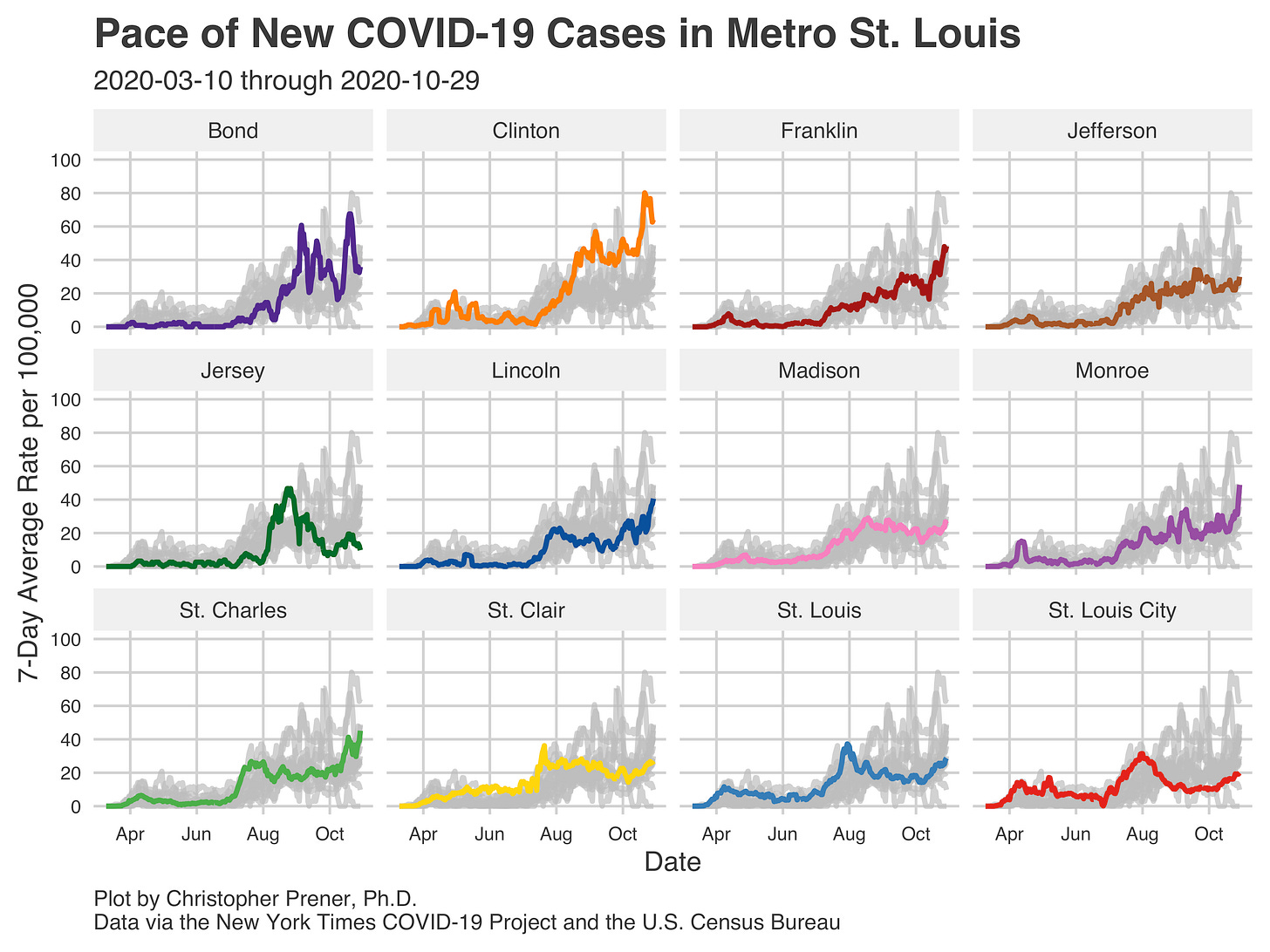

We’re now very near the all-time high for cases in this “Outstate” meso-region. We have also just hit a new all-time high for the Missouri counties in the St. Louis Metro area.

Geographically, the areas where we need to have the most considerable concern right now cover three parts of the state: Southeast Missouri (including Bollinger, Bulter, Madison, and Ste. Genevieve counties), Mid-Missouri as well as parts of the Lake of the Ozark region (especially Callaway, Cole, Maries, and Osage counties), and parts of Northern Missouri (especially Nodaway and Sullivan counties).

While the St. Louis Metro is not on this list, the overall number of cases here is rising and deserves attention, too. Franklin, Lincoln, and St. Charles counties are at all-time high rates of new cases. In Metro East, Monroe County is also at an all-time high for new cases. For both St. Louis City and County, the concern is that the seven-day average rate of new cases is climbing after remaining low for much of September. However, both rates remain well below neighboring counties’ numbers. St. Louis County is the most populous area, though, so the actual number of new cases is relatively high at nearly 300 per day on average right now.

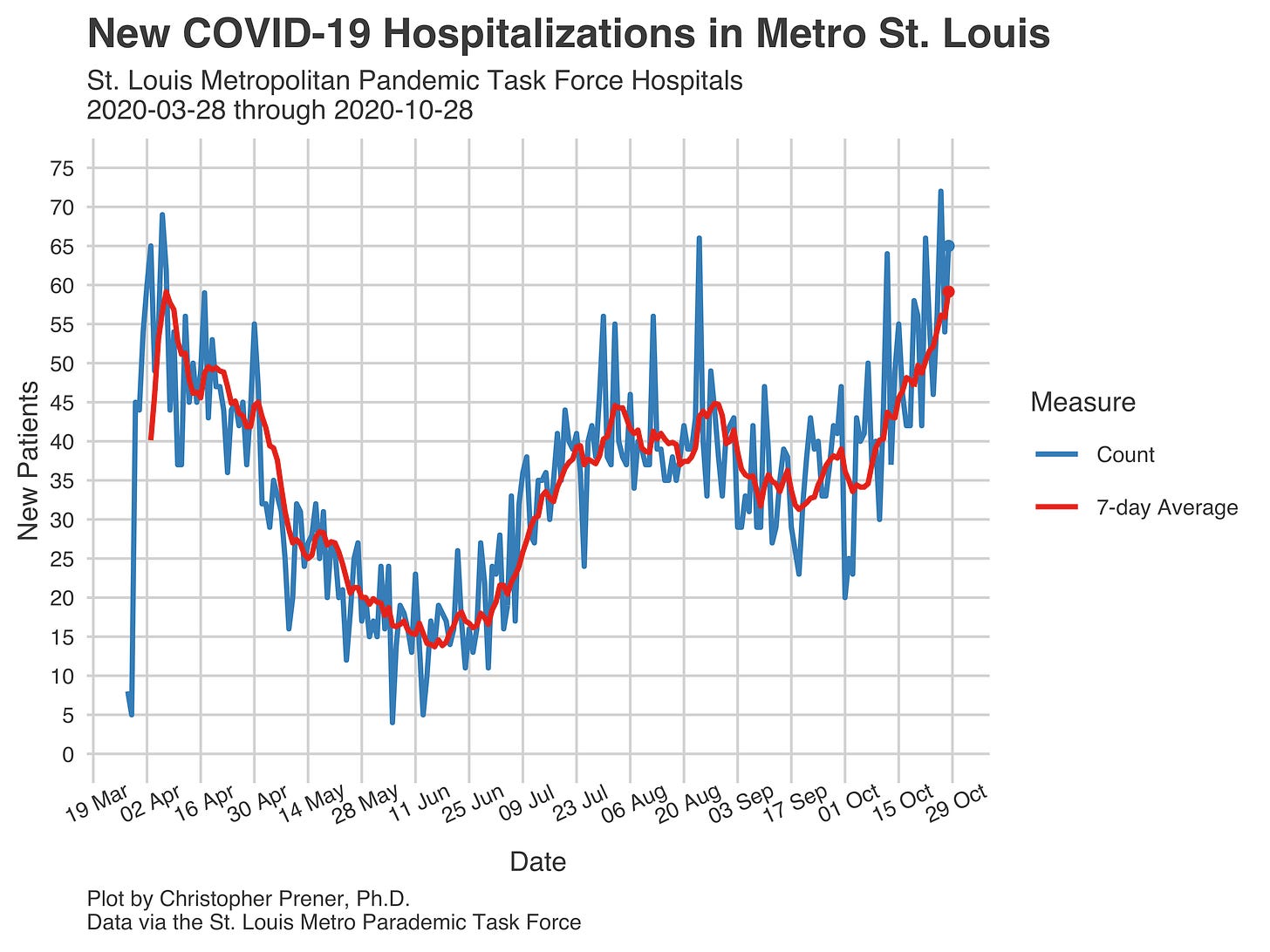

A consequence of this is rising hospitalization rates throughout Missouri. I don’t report the statewide hospitalization data because I have concerns about it. Not all hospitals report data every day, however. It is hard to tell whether small swings day-to-day is due to actual changes or are just noise from changes in the number of hospitals participating. The overall trend statewide is clearly upward from where we were, but more fine-grained assessments are hard to make.

In St. Louis, however, we have far more reliable hospitalization numbers, and they are not looking good. The numbers of new in-patients and the total number of in-patients have been trending upward, and the new in-patient seven-day average metric is now tied with its high point in April:

Like everything else, this has become political. Gov. Parson argues that hospitals have more capacity than some hospitals are claiming. This comes down to differences in licensed versus staffed beds. The Governor refers to the number of beds facilities are licensed for, while groups like the St. Louis Pandemic Task Force focus on beds they can actually staff appropriately, which are smaller. Dr. Fred Buckhold, gets into the larger pressures on hospitals right now in tonight’s interview, which is below.

Into the Weeds

With the election just days away, the folks at FiveThirtyEight have put together a guide to when we should expect election results by state. One thing I dislike about election night is the tendency to treat returns as a horse race - “candidate X was ahead, but now with County A reporting results, candidate Y is ahead.” This doesn’t reflect the reality of election data.

Instead, changes in the total vote share reflect state and local laws about when different types of votes can be counted. They also are affected by the speed at which precincts turn in tabulated votes. Demographic factors that influence how people vote, such as preferences for mail-in or absentee voting, especially this year, impact them too. One great thing about the guide FiveThirtyEight has created is that it provides some preview of how state results will change over election night and in the days that come after because of these factors.

Weekly Interview

This week’s interview is with Fred Buckhold III MD, FACP is an Associate Professor General Internist in the Department of Internal Medicine at Saint Louis University, specializing in the care of adults in both the clinic and hospital setting. He has been Residency Program Director for the Internal Medicine at Saint Louis University (IMSLU) Residency Program since 2014, where he is responsible for training 85 residents to enter the practice of Internal Medicine.

CP: What has it been like being a physician during the COVID-19 pandemic?

FB: Frankly, it has been a privilege. I think many internists such as myself have relished the chance to meet the challenge of facing an unknown disease and providing care to those in need. Granted, we were all very nervous about the unknowns and worried for our own safety and that of our families. As we have gained experience, we feel more comfortable dealing with COVID. That said, like many others I think we have grown tired of social distancing and not being around colleagues to collaborate and learn like we are used to.

CP: Do you see COVID having a long-term impact on the health care workforce?

FB: Absolutely. The entire system was already ailing - higher financial pressures, high levels of burnout and mental distress in the workforce, and an insurance system that is amoral and frankly falling apart. COVID completely laid bare all of those issues - leading to healthcare layoffs, possible financial ruin, and increase work-place duress. COVID has had this bizarre effect of reinforcing why we do this important work yet making the massive flaws in the system (and the system's reliance on the altruism of doctors and nurses) much more obvious and frankly, deadly. I feel that COVID has shown the importance of having a highly trained work-force who can adapt to changes and making sure that society nurture the asset of having such highly trained professionals

CP: What is one thing that you see missing from discussions about COVID-19?

FB: What is not said enough is the catastrophic failure of leadership on a state and national level in many places; not the political discussion but the voice of doctors and nurses saying this was a travesty (note the New England Journal of Medicine, our pre-eminent journal, had an editorial stating this). As a corollary, we've also lost faith in highly reputable government organizations such as the CDC, which honestly makes me just sad.

The other issue is the ticking time bomb of healthcare facilities - a number of places had started to close prior to COVID - with state budgets under threat next year due to lower tax revenue (and tax increases being unlikely) Medicaid and Education funds (many academic hospitals are with state schools) are likely to be reduced, inducing more financial stress on the healthcare system.

Editor’s note: we’re especially concerned about these closures in rural areas where there may only be one facility. In Missouri, we’ve had at least seven rural hospitals close since 2014.

CP: What is something giving you hope right now in terms of COVID-19?

FB: I'm proud to be part of a profession and have a group of physician and nursing colleagues who did an unbelievable job in tough circumstances with limited (and at times worryingly unsafe levels of) resources. During my first rotation in our COVID unit in April, I was in awe of what our nurses and other clinical staff were doing. I also thought the healthcare community in St. Louis came together and worked to share learning and resources and that to me was a huge positive. Despite the ongoing issues we face as a country, crises still demonstrate that people are inherently good and want to help each other. We are a generous community, and that showed in a lot of ways when everyone was stressed.

Last, I think COVID demonstrated the power of medical science. Within a year of the onset of a global outbreak, we identified quickly the organism, targets for therapy, tested therapeutics with rigor, and before the end of the year could feasibly have a vaccine that prevents the spread of COVID-19. That is unprecedented, and frankly, an unbelievable testament to our scientists and physicians who have charted this path.