In this week’s edition of River City Data, I provide some updates on the latest numbers and trends, announce a greatly expanded ZIP code map for the St. Louis Metro, geek out on election polling, and share my interview with the St. Louis Post-Dispatch’s Michele Munz. Enjoy! - Chris

COVID-19 by the Numbers

Total cases in MO: 204,951 (+17,147 from last Friday)

7-day average of new cases per day in MO: 2,873.14 (+596.43 from last Friday)

Counties with the highest per capita rates of new cases per day this past week:

Sullivan (149.26 per 100,000), Cole (120.63), Pettis (112.95), Nodaway (108.35), Osage (102.8), and Cooper (98.09)

Total deaths in MO: 3,197 (+183 from last Friday)

7-day average of new deaths per day in MO: 31.29 (-4.43 from last Friday)

These numbers are current as of Thursday, November 5th. Additional statistics, maps, and plots are available on my COVID-19 tracking site.

New on the COVID-19 Tracking Site

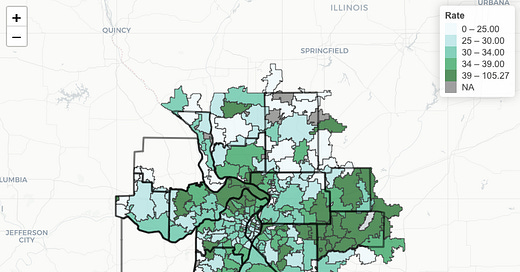

I have a new map product that I am very excited to share here first - a greatly expanded ZIP code map of cases in the St. Louis Metro area. All Metro East ZIPs and those in Warren County are now available on the cumulative rate map. These will be added to the 14-day rolling average map next Friday. I’ve spent the week touching base with both Lincoln and Franklin counties, and am excited to share that their data will be coming to both of these maps soon, too!

Future updates for this year are going to include:

Next week - excess mortality plots made by my pal Tim Wiemken, covering both the U.S. and Missouri

Next few weeks - comparison of deaths between actual date and the date reported on the State’s dashboard, as well as age breakdowns for both morbidity and mortality statewide and in a few key counties

In early December - a similar ZIP code map for the Kansas City area (covering Kansas City as well as Jackson, Platte, Clay, Johnson, and Wyandotte counties)

Summary for the Week Ending November 6th

The pace of new cases in Missouri is picking up dramatically. In last week’s email, I reported that we had seen 12,972 new cases added to our total in the prior week. In this week’s email, that number is 17,147. One positive is that the number of recent deaths is actually smaller than it was this time last week, but remember that this is a lagging indicator, so we expect it to rise weeks after cases begin to trend upward.

We can see this increased pace reflected in the three “meso” regions that I track new cases in:

We’ve set all-time highs in each of these regions over the last few days. Today, Dr. Alex Garza emphasized the trend I’ve been observing, too. “There is really no safe harbor now, whether it’s rural, suburban or urban — we’re seeing admissions from all over,” he noted. Indeed, our 7-day averages at the county-level are showing widespread numbers of new cases in basically every corner of the state:

The areas of most significant concern are in the Cape Girardeau and Bootheel regions as well as Mid-Missouri (broadly defined to include the Lake of the Ozarks area) and portions of Northern and Northwestern Missouri. Nodaway and Sullivan counties now have the highest cumulative per capita rates in the state. But again, basically every county’s trajectory is concerning right now.

There are two trends in St. Louis that are also worth noting. First, we’re seeing a resurgence of cases in St. Louis City and County. This is a relatively new trend, and these upticks quickly escalated to an all-time high in St. Louis County. They also come at the same time we’re seeing all-time highs in Franklin, Jefferson, Lincoln, and St. Charles counties:

One practical consequence of this is that our hospitalization numbers in St. Louis are reaching levels we last saw in April and early May. For example, our total in-patient numbers have surpassed 600 for the first time since the early days of the pandemic:

Protecting our hospitals, which are operating at about ninety percent capacity here in St. Louis, is not just a local problem. Our hospitals are currently admitting patients from Mid-Missouri, Southeast Missouri, and the Bootheel. If we lose the ability to accept transfers, patients in “outstate” Missouri (where health care access can be more limited) will suffer. And a crush of patients in St. Louis means our health care system will come under increasing stress in ways that it cannot support even in the short term.

The good news is we have the power to change this trajectory. Wearing masks, physical distancing, and avoiding time indoors with people not in your household are all ways we can bend the curve again.

Into the Weeds

With the election still unfolding around us, I want to touch quickly on two data-related points. First, we’re starting to see exit polling data released with demographic data on who supported different candidates. I want to emphasize that these are preliminary. It is also critical to understand that, while firms have conducted phone interviews to try to correct for the large numbers of mail-in ballots, there is a real reason to be warier of exit polling than usual.

Second, we’re already litigating the accuracy of polling. There are really two debates here - did polls correctly predict a race’s winner, and did they accurately predict the margin? In the presidential contest, Florida certainly looks to be a circumstance where polling did not correctly predict the winner.

However, the real interest is going to be whether the margins were accurately reflected by both individual pollsters as well as polling averages and models. Pennsylvania, for example, is much closer than the polls suggested.

For now, we need to take a big, deep breath. We do not have final vote counts in many races yet, so it is hard to assess just how far off the polls were. Moreover, we expect polls to be wrong - Nate Silver of FiveThirtyEight describes this as “normal polling error.” So, we need to reframe our expectations - the question isn’t whether the margin was correctly called, but was the prediction by a pollster or an average within a normal polling error of the outcome?

We also need to parse out what polling errors might be specific to the pandemic, something pollsters were worried about. These errors are not likely (knock on wood) to be a factor in future races, unlike declining phone survey response rates. I’ll continue to share “postmortems” as we get them from groups like Pew, FiveThirtyEight, and The Upshot. In the meantime, be wary of exit polls, and don’t dismiss political polling just yet!

Weekly Interview

This week’s interview is with Michele Munz. Michele has been a reporter for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch for almost 22 years, the past 10 covering health and medicine. As a health reporter, Munz has won awards for her coverage of midwifery care, an experimental treatment for ALS and the opioid epidemic. She was the St. Louis Newspaper Guild’s 2015 Terry Hughes Award winner.

CP: What has it been like being a reporter during the COVID-19 pandemic?

MM: When the pandemic first hit the U.S. and businesses and schools started shutting down, I knew that it was going to completely consume my job as a health reporter for months to come. Being a reporter right now feels overwhelming. Between keeping track of the daily data, the changing science, holding public officials accountable and the human impact — the stories that need to be done are endless. We are all working very hard, as the pandemic touches on every reporter’s beat, not just health.

CP: How else has the job changed?

MM: We are all working from home, and I really miss being around my colleagues and the bustle of the open newsroom, where split-second decisions are often made by screaming among desks (it really is like the movies!). But more than anything I miss going into homes, offices, hospitals, events and observing and talking at length to people face-to-face. It’s what I love most about being a reporter and what makes stories so much better.

CP: Do you see COVID having a long-term impact on journalism?

MM: I fear some negative impacts of COVID-19 on journalism, in terms of how our elected officials and public servants communicate with reporters. Public relation hires have increasingly over the years been getting in between journalists and government with press releases, controlled press conferences and emails. They are also more easily able to circumvent the press with their social media platforms. The pandemic has made that even worse as journalists are more pressed for time and officials feel they can more easily avoid interviews. I hope that this does not continue.

CP: What is something giving you hope right now in terms of COVID-19?

MM: What gives me hope is that I feel like the pandemic has made people realize the importance of local reporters and their hometown newspaper. We have more people than ever realizing what a great resource we are, and relying on us to tell them about the issues and stories that impact them the most. Readers see we need more feet on the ground and are subscribing so we can keep and hopefully hire more reporters.