Tonight’s newsletter takes in the latest data, which are really our first stable look at case data since before Thanksgiving. I share an excellent KCUR article about Missouri’s data woes in the “Into the Weeds” section, which is a perfect segue to my interview with St. Louis County epidemiologist Andrew Torgerson.

- Chris

COVID-19 by the Numbers

Total cases in MO: 353,082 (+22,637 from last Friday)

7-day average of new cases per day in MO: 3,937.57 (+193.14 from last Friday)

Counties with the highest per capita rates of new cases per day this past week:

Benton (147.45 per 100,000), Worth (147.06), Harrison (133.6), Gentry (117.89), Buchanan (115.79), Carroll (109.85), and Marion (108.12)

Total deaths in MO: 4,690 (+315 from last Friday)

7-day average of new deaths per day in MO: 59.43 (-2.29 from last Friday)

These numbers are current as of Thursday, December 10th. Additional statistics, maps, and plots are available on my COVID-19 tracking site.

Summary for the Week Ending December 11th

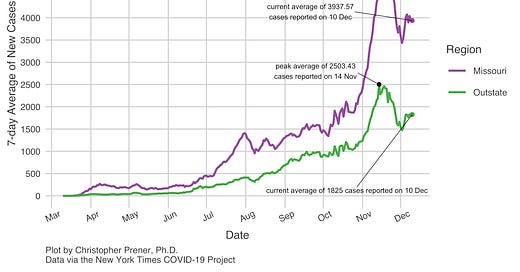

From a data perspective, our standing tonight is a significant improvement over where we were last week. You can see the large drop post-Thanksgiving in the trends below, followed by a significant upward correction and then a group of small “squiggles” (yes, this is the technical term!).

To return briefly to last week’s newsletter, I described the initial drop to about ~4400 new cases per day on average statewide as a genuine decrease. However, I was skeptical of the ensuing drop to ~3400 new cases per day on average. The reversion we saw this week back up to right around 4000 cases fits with that skepticism. Our testing environment has mostly recovered from its Thanksgiving week dip. So, I have some confidence that our picture right now is more accurate than this time last week.

What’s causing this drop? We can only speculate, of course. It may be that more folks stayed home on Thanksgiving than we feared, though there is still time for those cases to start filtering into my data. It may be that the alarm bells that were sounding in St. Louis and Kansas City about hospital capacity before the holiday have affected some behavior. Colleges sending students home for the holidays, and in many cases asking them not to return, may also be contributing to a portion of the decrease.

We should not, however, let a focus on drops obscure concerning patterns happening in Missouri. Take metro areas, for example. As you can see below, we’ve had durable decreases in Cape Girardeau and Jefferson City in particular.

But there are also some warning signs here. Metros like Kansas City, Springfield, and St. Joseph have seen increases back to basically where they were in mid-November. Columbia has also seen a strong resurgence in cases despite the large drop. Like Cape Girardeau and Jefferson City, it is still among the highest per capita rates of new cases among our metro areas. Not only are they high in relative terms, but per capita rates of this magnitude before late October were unheard of in Missouri at the metro level.

The same pattern is playing out at the county level as well. If you take in the map of new case rates over the last week, you’ll see that the same regions, by and large, are still contributing the most cases to our statewide rate.

In Southeast Missouri, rates have dropped significantly. However, several counties are still posting new case rates between 80 and 100 new cases per day per 100,000 residents. Around Lake of the Ozarks, rates are the highest they’ve been (or close to that point) in Benton, Laclede, Morgan, and Pulaski counties. Around Joplin, in contrast, new case rates have dropped substantially from prior highs.

In the Northwest Missouri region, we have a microcosm of all of these patterns. Harrison County saw a large Thanksgiving drop followed by a steep resurgence in cases. Atchison County saw a similar decline with no resurgence. Buchanan and Gentry counties are near all-time highs, with rates of new cases over 100 new cases per day per 100,000 residents. Daviess and DeKalb counties have relatively low numbers similar to rates in Kansas City and St. Louis County.

In both these large jurisdictions and the City of St. Louis itself, case rates have declined somewhat. However, they are still higher than at any point before mid-November. This final point is why hospitalization rates remain so high in the St. Louis area. We’ve seen some small decreases from our mid-November highs, but not nearly enough of a drop regionally to take the pressure off our hospitals. ICU capacity as of today was 90% full (per the St. Louis Pandemic Task Force).

Aside from this, mortality rates are pushing higher statewide and in the St. Louis area as well. So, take a small breath because new case rates are down statewide, but remember that there is a lot of variance within the state. Moreover, even when cases are down, they’re still high relative to most of the pandemic, and some areas are at all-time highs. Even worse, other metrics, like hospitalizations and mortality, are very high as well. In short, we cannot let down our guard now.

In the Weeds

KCUR’s Alex Smith has an excellent article, out yesterday, about the effect of poor quality hospital data in Missouri on the trajectory of the pandemic. Alex highlights a problem that has been a concern for months - Missouri was one of the only states without an independent means by early summer to collect in-patient census data from hospitals. We were without data for more than two weeks when the federal government changed data collection processes this summer. And the state’s data still don’t match what the federal government reports. Alex’s reporting walks through all of this, and I highly recommend the article!

Weekly Interview

This week’s interview is with Andrew Torgerson, MPH, who has been an infectious disease epidemiologist with the Saint Louis County Department of Public Health since 2016. Before starting his career in public health, he worked as an emergency department technician, including five years at SSM St. Mary’s Health Center in Richmond Heights.

CP: Can you tell us a bit about your educational background, and what you did day-to-day pre-pandemic in your role?

AT: I have a Bachelor’s in English and a minor in biology from Saint Louis University and a Master of Public Health with a focus on epidemiology and biostatistics from Washington University in St. Louis. I also received a Certification in Infection Control in 2019.

Until January or February of this year, my work focused mostly on sexually transmitted infections and hepatitis C. I wrote annual epidemiological profiles of those diseases, tried to keep up on relevant research and news, and supported our prevention programs and community partners with data. Occasionally, I’d get involved in more policy-related work, like contributing to a white paper that our department wrote about the public health benefits of syringe services programs.

When the pandemic began, I was in the early stages of a project to match birth certificate data with hepatitis C case reports and try to estimate the incidence of perinatal hepatitis C in St. Louis County – I hope I can pick that up again at some point in 2021.

CP: How has the pandemic changed your role – what do you do day-to-day now?

AT: It’s changed over time. At the beginning of the year, I spent a lot of time interviewing and monitoring people who were returning from travel in China and other early hotspots, and I facilitated testing for people through the state public health lab.

In mid-March, though, I became our de facto COVID-19 surveillance lead, and that’s been my main job ever since. I update the surveillance data on our website every morning, give daily updates to our department’s leadership team, provide other parts of the county government with data, respond to lots of one-off data requests and questions. I write a detailed surveillance report every two weeks to make sure we stay on top of changes in the epidemiology of the outbreak.

Those are the deliverables, but I seem to spend most of my time trying to get to the bottom of data quality problem or another. “Wait, did testing volume really double on Tuesday, or is something wrong with the data we received? Why are we suddenly getting five times as many cases among people of ‘other race’ – that seems unlikely. Why did this lab send us hundreds of test results with names and dates of birth missing?”

CP: What are some of the challenges you’ve faced reporting COVID data, particularly to the public?

AT: Oh man, this could be an entire interview. I’ll try to cover a lot of ground.

Balancing quality with timeliness. Everybody understandably wants to know what’s happening right now, but each COVID-19 infection unfolds over weeks and months, and information doesn’t always reach us as quickly as we’d like. Somebody who gets infected today probably won’t show up in our case counts for a week at the earliest. We want our data to be current, but we don’t want to release information that’s so incomplete that it’s useless or misleading. It’s a tricky needle to thread.

Managing expectations. Any information beyond test dates and basic demographic information has to be gathered through case investigation, which is time- and labor-intensive. We currently have far more cases than we can investigate, so we have to make compromises in terms of how many people we can interview and how much information we try to collect about each one. Plus, we prioritize certain cases for investigation instead of taking a random sample, so the information we gather isn’t necessarily generalizable.

Responding to demands for extremely granular data. When transmission is this widespread, we should be making decisions based on the broad trends. Really fine-detailed analyses aren’t going to be particularly valuable until overall incidence is much, much lower than it is right now.

Dealing with misinformation and disinformation. I probably don’t need to elaborate here.

CP: Something that has gotten a bit of attention is the role that fax machines still play in sharing public health data. Can you talk a bit about the data systems we have in MO, and where we need to look for improvement?

AT: I’ll have to be broad – this could be a whole interview unto itself, too. The fundamental problem with our public health data systems is that they don’t scale well. Surveillance data are stored in a straightforward relational database, but that database relies heavily on manual data entry – electronic lab reporting and electronic case reporting exist, but they’re not widely implemented, so a huge amount of reporting consists of faxing a case report form or a printed-out lab result to the health department. That’s fine for a few hundred Ehrlichia cases or a few thousand Salmonella cases per year, but it’s utterly unmanageable for tens of thousands of COVID-19 cases per week.

The state health department has made considerable improvements to their systems this year, but they were reacting instead of preparing and it naturally took some time to implement those improvements, which led to data getting fragmented across multiple state and local systems.

As for where we should look for improvements, I’m not sure! To be clear, every state seems to have this problem to some degree. While Missouri has one of the worst-funded public health systems in the country, I’ve never met anybody at a conference who says, “oh yeah, my state/county has fantastic data infrastructure!”

CP: What is something giving you hope right now in terms of COVID-19?

AT: Vaccines! The short-term outlook is bleak, and I’ve grown increasingly pessimistic about the chances that we’ll all pull together and do the things necessary to protect each other over the next several months until vaccination is widespread (please, please prove me wrong, St. Louis!), but the news that there are multiple highly effective vaccines coming our way means there’s finally something to be hopeful about. I’m thrilled about that.