Tonight’s newsletter is the last of 2020 for me. I’ll be taking the next two Fridays off to spend some time with my family. Regular followers of the website should note that updates to the site will be paused between December 24th and 28th and between December 31st and January 3rd.

In early January, my Friday publishing schedule will vary - we’ll be moving back to St. Louis from where we’ve been in upstate New York since May. I’m going to prioritize at least one early January newsletter issue. I’m hoping to return to regular newsletter postings in about a month. I appreciate your patience in the meantime.

Tonight’s newsletter is a bit different - there is no interview tonight. Instead, I’ll share some lessons learned over the past year about how we handle and communicate public health data. But first, I’ll provide a breakdown of the latest numbers and some commentary on the “post-Thanksgiving bump” in cases we experienced. I hope you and your families have healthy, joyous New Years, I’m grateful for your readership, and I’m looking forward to the next issue of River City Data in early January!

- Chris

COVID-19 by the Numbers

Total cases in MO: 378,014 (+22,867 from last Friday)

7-day average of new cases per day in MO: 3,561.71 (+32.86 from last Friday)

Counties with the highest per capita rates of new cases per day this past week:

Howell (141.43 per 100,000), Cape Girardeau (106.15), Gentry (102.88), Schuyler (98.37), Harrison (93.52), and Carroll (90.47)

Total deaths in MO: 5,101 (+397 from last Friday)

7-day average of new deaths per day in MO: 58.71 (+11.71 from last Friday)

These numbers are current as of Thursday, December 17th. Additional statistics, maps, and plots are available on my COVID-19 tracking site.

Summary for the Week Ending December 18th

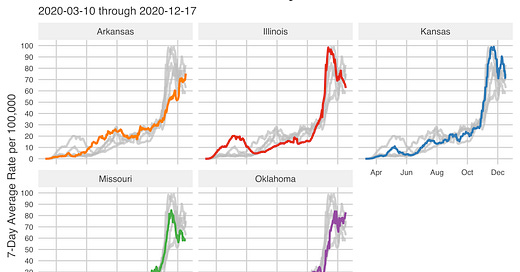

We’ve been waiting to see if Missouri experienced a jump in new cases after Thanksgiving. I think it is safe to say that yes, we did, and that bump has started to recede. Missouri, Illinois, and Kansas all have the same notable pattern in their statewide per capita rates of new cases:

All three states saw a mid-November peak in new case rates that were all-time highs. They receded after Thanksgiving, all likely driven by a slowdown in testing. Then, the rates swung back up in early December as new infections were identified at greater rates again to one degree or another. Some of these were likely delayed positives from Thanksgiving through the weekend after. Still, some of this was probably a slight acceleration in new cases resulting from the holiday itself.

At least in Missouri, one possible explanation is that dire warnings about hospital capacity had their intended effect, reducing the numbers of Missourians who gathered together for Thanksgiving. The downside of a minimal bump is it may be misinterpreted for Christmas and New Year’s as a license to gather because “Thanksgiving wasn’t that bad.”

One key caveat about the downward shift is we risk missing the forest for the trees. Statewide and in all three regions I track new cases in (St. Louis, Kansas City, and “Outstate”), the rates of new cases still remain higher than any point before early November.

So, declines are great, but make no mistake, things remain very, very challenging in Missouri.

It’s also worth pointing out that not all areas of Missouri have had drops in cases that mirror the statewide trend. Greene County and the area around Springfield is one worrying area where we’re setting all-time highs despite the statewide trajectory:

Just a bit to the south and east, in the Ozarks, Howell and Oregon counties have seen pronounced mid-December spikes that occurred after much of the post-Thanksgiving spike had passed. Other counties near them, like Ozark, Texas, and Wright, are also seeing spikes though they are much smaller in scale:

Cape Girardeau county is seeing something similar, as are neighboring Perry and St. Francois counties (though to a far lesser extent):

Ste. Genevieve County, like the statewide and regional patterns, is experiencing significant declines as well. Still, again, their rates remain well above anything we saw before early November.

As we head out of one holiday week for Hanukkah and into another holiday week for Christmas, we’re doing so in a different context than we were for Thanksgiving. Things are not as bad as they were before Thanksgiving. However, they are only marginally better and remain worse than at any point before early November. Mortality is steadily increasing. Hospitalizations remain high in the St. Louis area. I worry that apathy in the wake of Thanksgiving potentially makes Christmas gathers even more of a risk.

After Thanksgiving, we had a real delay in returning to a “normal” data environment. We had very low numbers reported over the weekend after the holiday and a large dump of new cases on the following Monday. I expect similar patterns to follow Christmas and New Year's day. Since they’re back to back, and both on Fridays, January 12th is the date I have for our first “clean” seven-day averages. This is one of the most frustrating pieces of the pandemic data situation for me - in the wake of particularly dangerous points, holiday gatherings, we have the greatest amount of uncertainty in our data.

In the Weeds

Regular readers know that I’m particularly interested in election polling. I’ve been waiting for postmortems to come out breaking down what went right and wrong with our polls during the 2020 election cycle, and I missed this great write-up by the folks at Pew Research.

It isn’t quite over yet, either, given that we still have two runoff elections in Georgia. In the past, the GOP has gained ground during runoff elections in Georgia. However, there is reason to think the electorate in Georgia has undergone a significant shift in the last few decades. Keep both trends in mind as we approach the January 5th runoff.

Parting Thoughts for 2020

I’ve been tracking COVID-19 data since March 24th - nearly eight months now - and have spent quite a lot of time thinking about what works well and what does not work in terms of how we report data to the public. These are five things I’ve landed on so far as lessons learned from this work:

We have a lot of great tools to draw on. We’ve seen counties and states stand-up dashboards using ArcGIS, Tableau, and Microsoft PowerBI. All are capable tools, though each has some drawbacks as well. The tool agencies pick for communicating data are secondary to focusing on clear narratives and using best practices, like displaying rates per capita instead of counts.

Unfortunately, many folks who work in public health departments don’t learn many of these skills needed in graduate school. I don’t think we need to teach Tableau in MPH programs. By the time we get to the next pandemic, some other tool will be king. But the fundamentals will still be the fundamentals.

The old programming adage “garbage in, garbage out” also has a lot of relevance for public health data. We have a system that relies heavily on fax machines and, and Andrew Torgerson said in last week’s interview, doesn’t scale well. We need to invest heavily in data and IT infrastructure for public health agencies. They need to be able to rapidly collect test results, report deaths, and identify signs of emerging health disparities. This means accurately collecting address, racial identity, gender, and other indicators that we need to observe. When these fields are present, they’re too often left blank right now.

We need better systems for communicating regionally. Some of the niche I have filled sits between what individual counties provide and what the state provides as a whole. I have the only regional map of ZIP code data for the St. Louis metro, and have been working on a similar product for the Kansas City metro. Unfortunately, we don’t have any “official” entities that appear to be concerned with stitching multiple jurisdictions’ data to approximate the activity spaces people actually use.

We need to embrace sharing data. The amount of time my students and I have spent building “web scrapers” - tools that wind their way through websites’ HTML code searching for data - has been significant. It is error-prone. At least once per week, something on one of the many sites I scrape changes and breaks our code. This would all be rendered moot if agencies made their data downloadable. Missouri has made some strides here, but what they offer for download is just a fraction of their data on the dashboard.