Due to the data issues that I discuss below, I am not providing an update to specific numbers tonight for cases and deaths in Missouri. Detailed data will return next week. Instead, I discuss these challenges, provide an update on vaccinations in Missouri, and share reflections from myself and several friends of the newsletter describing those moments a year ago when the pandemic became real for us.

I also want to share a longer set of questions I answered for the COVID-19 Data Hero awards. If you’ve wondered how I do some of the COVID work I do, please check it out! Speaking of that work, a few things will be changing. Starting tonight, River City Data will be coming out on Thursday, and I’m changing to one Twitter thread per week on Tuesdays. Weekends will see the website updated, but no social media activity. I hope these just as detailed but slightly more infrequent updates continue to be useful to you! - Chris

Summary for the Past Week

This last week has been a busy one on the data front. We saw several changes to state and local data sources that I want to summarise here. First, Missouri began providing antigen test results at the county level. This clarifies a significant portion of uncertainty discussed in this newsletter several times since January. Antigen tests are the so-called “rapid” tests that can return results in as little as fifteen minutes. Some jurisdictions have been reporting these all along in their data, but most counties and Missouri have not been sharing these counts of “probable” cases with the public.

The impact of these new data is significant. Approximately 80,000 new cases were reported with this update to the State’s dashboard. About 50,300 of those cases were not being reported in my data. The discrepancy is because my primary data provider, the New York Times, was getting some county data directly from local health departments. Since these local health departments (especially in the St. Louis area) were including probable cases all along, the number of new cases in my data sets is substantially below the number of new cases reported by the State. About 7,200 of these newly identified cases in my data originated from counties in the St. Louis metropolitan area, 14,600 were in the Kansas City metro, and the remaining 28,500 were “outstate.”

Second, Missouri began administering the Johnson & Johnson vaccine recently, which is excellent news for all of us. On Monday, at the same time that Missouri’s main dashboard was updated with antigen tests, the vaccination dashboard was also updated to reflect that we now have both one and two-dose vaccination regimens.

Third, the St. Louis Pandemic Task Force stopped reporting data on Saturdays and Sundays. While this is a very understandable decision from a personnel standpoint (staff contributing to their efforts have been working tirelessly), it does mean we miss out on key data. The Task Force provided me with data for those missed metrics on Saturday and Sunday for the past weekend, and I will be able to continue “filling in” these values on Mondays moving forward.

Fourth, we identified some out-of-date sources for our Kansas City ZIP code map. This has not been updated yet on the site itself, but our data sources are now all up-to-date again.

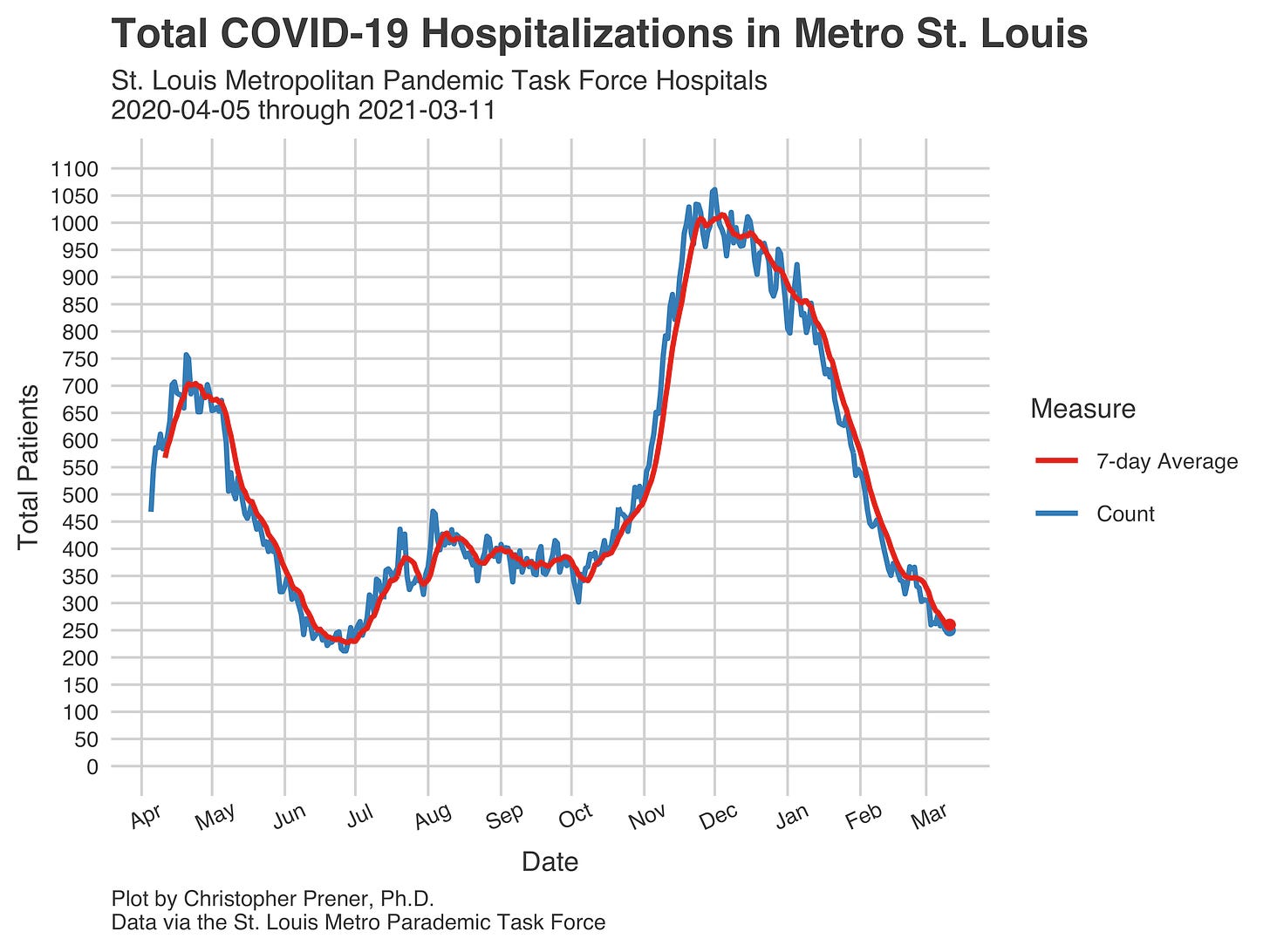

These big changes mean challenges for reporting data to you all. I have been working over the past few days to update my systems and hope to return to nightly updates by early next week at the latest. I can share that our statewide numbers continue to decline, as do our local hospitalizations here in St. Louis.

The downward trajectory in our hospitalizations gives us a good sense of where things stand now and the relative size of the peaks in the spring and again in the fall. Our current numbers are roughly the same as our all-time lows in mid-June.

Vaccination Update

We have the best picture of vaccinations across Missouri so far this week. The pattern of complete vaccines continues to show geographical disparities - higher rates across Northwest, Northeast, and Mid-Missouri as well as around the Cape Girardeau area. Some counties are now approaching 18% of their populations fully vaccinated, while others have just around 2% of their population vaccinated.

Recent assurances that we will see a shift in vaccination distribution are beginning to show changes to these patterns, however. Counties in the St. Louis and Kansas City metropolitan areas, around Springfield, and in Joplin all show higher rates of new vaccinations.

I am concerned, however, that St. Louis City itself still has a relatively low rate of new vaccinations over the past week. When we look at these same data by Highway Patrol District, the area St. Louis is located in, District C, remains in the middle of the pack regarding new vaccination rates.

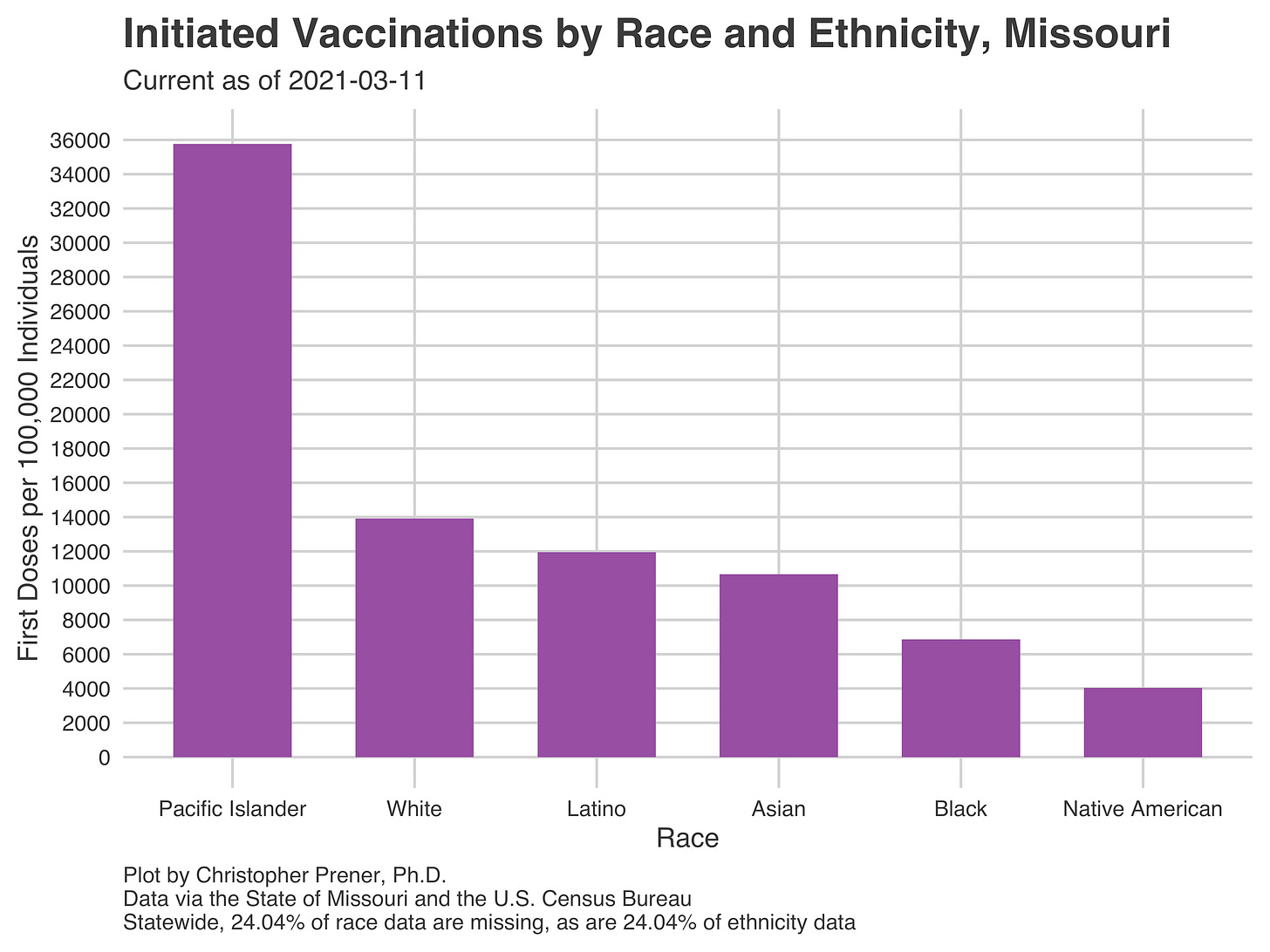

These lower rates in St. Louis, Kansas City, and Bootheel counties with higher proportions of African American residents are also reflected in the racial disparities we see in those who have received at least an initial dose of the COVID-19 vaccines.

Distilling this down to “hesitancy” is a mistake (and I dislike the term). There are significant structural barriers to accessing vaccines and longstanding experiences of racism in the health care system that can help us understand why disparities are persisting.

Reflecting on the Past Year

This past week marks one year of confirmed COVID-19 cases in Missouri. For many of us, it also marks a year of taking precautions to keep ourselves safe. I asked several of the folks who had participated in interviews here to reflect on when the pandemic became real for them, and have included those below.

Chris

For me, it was March 8th, 2020. We had this moment on the way to the Magic House’s maker space where it hit us that we should start to prepare for real disruption. We went to Costco, and I vividly remember talking to my wife Johanna about whether Saint Louis University would have our students remain off-campus after Spring Break ended.

The discussion felt far-fetched, but just a few days later, the decision was made for students not to return to face-to-face instruction. My daughter went to pre-school the following week. It was spirit week, and she dressed up as “twins” with her best friend on Friday, March 13th. That was the last day they would see each other until January. By the following Monday, just over a week after our Costco run, I was packing our car with books, computers, and office supplies as I moved out of my office on campus. I’ve only been back three times since, all since January.

Rachel Winograd, PhD, Missouri Institute of Mental Health and the University of Missouri-St. Louis (Interview)

This pandemic got real for me on March 10th, 2020, while I was eating a burrito at a Chipotle in Jefferson City and looking at my phone. I was reading an article in The Atlantic that had just come out, "Coronavirus: The Case for Canceling Everything." The looming threat and sense of urgency that was jumping out of the article was in stark contrast to where I was and what was happening around me. Lots of people were in that Chipotle, sitting close to each other, laughing, eating, touching stuff... A guy next to me sneezed and when people turned to look at him, he waved his arms in the air and went "Oh no I have the Coronavirus you better freak out!!" and everyone laughed.

After lunch, I was heading to a meeting in a windowless conference room with 25 other people. How did this track with what I was reading? This journalist was sounding the alarm that this virus is real, it is here, and it is going to tear through our communities before we can catch our breath unless we act fast. Like, today. One quote struck me: "...anyone in a position of power or authority, instead of downplaying the dangers of the coronavirus, should ask people to stay away from public places, cancel big gatherings, and restrict most forms of nonessential travel...the responsibility for social distancing now falls on decision-makers at every level of society."

In my role at UMSL, I directly or indirectly supervise 15-20 people on our Addiction Science team, and I knew they were all back in St. Louis, working in our office, sitting in meeting rooms together, and going about their business. In this moment, the gravity of what was about to happen started sinking in, and I promptly sent an email to the whole team telling people to pack up and head home to work remotely "until further notice." I figured it would be a couple of weeks until we were back in the office. I ended the email by saying, "Let’s hope this blows over and remote work proves to be an overreaction... in the meantime, wash your hands and enjoy your sweatpants."

Andrew Torgerson, MPH, Epidemiologist at St. Louis County’s Department of Public Health (Interview)

I remember skimming notices in ProMED about an unexplained cluster of respiratory illnesses in Wuhan, China in early January 2020, then getting increasingly alarmed reading Laurie Garrett’s Twitter feed over the next couple of weeks. By the end of the month, my colleagues and I were interviewing and monitoring returning travelers from an ever-expanding list of countries, advising them on isolation and quarantine protocols, making sure we could arrange for testing if one of them developed symptoms, etc. I had done the math in terms of the ballpark numbers of cases and deaths we should expect given the conceivable ranges of attack rates and case-fatality rates, and I knew it would be catastrophic, but I didn’t have enough imagination to think about how drastically our day-to-day lives would change.

The thing that jolted me out of that was listening to Nancy Messonier at CDC say during a briefing on February 25 that she had told her family that they should prepare for “significant disruptions of their lives,” which about as dramatic as a CDC press briefing ever gets. Within 30 days of that briefing, St. Louis County went from 0 cases to more than 200 (and two deaths), our first stay-at-home orders had been issued, and everything changed.

Steve Edwards, MHA, CEO of Cox Health (Interview)

Like so many, I watched the initial news from Wuhan and discounted worries about it becoming a pandemic. It was a curiosity, something China would contain, after all, they had the advantage of strong state control, the sort of power needed to shut down an epidemic. As the news began to come from the northern Lombardy region of Italy, and Madrid, Spain, both open countries with a free press, I became shaken. This was real.

In early March one of our surgeons, Jose Dominguez, told me his cousin was the director of an ICU for a private hospital in Madrid. I asked if I could visit with her, Amaya Dominguez, and he made arrangements and began to text back and forth with Dr. Dominguez helping to translate.

I asked Amaya what do I need to know, what supplies do you worry about, what unexpected problems? She shared pictures of their PPE supply room, with disposable masks hanging to dry as they were assigned one per week. I saw the swim goggles they were using for eye protection and saw images of nurses wearing what looked like trash bags for protection. She told me that they were using many times the normal amount of oxygen, and the police had to shut the street down as it was the only place to locate a giant portable oxygen tank. She also said the morgue became overburdened, and the city shut down the ice skating rink to make it a morgue.

In an election year in the United States, it appeared the right-leaning media was downplaying the pandemic and the left-leaning media was possibly amping it up. It was hard to know what to believe. Amaya brought a personal light to the severity of the pandemic that made it very real to me. I credit her with instilling a fire in our organization, which ignited our orientation. We secured ventilators, PPE, paralytics, antibiotics, and quickly built emergency ICU space in the event the pandemic spread to our part of the world. Of course, it did, and we were given the gift of time and the inspiration to prepare. So much credit goes to this brave nurse in Madrid Spain who helped her cousins hospital in Springfield, Missouri.

If you like what you see here and don’t already, please subscribe!